Might come in handy some day: tips for seducing Zell Miller.

Detached Observer

logic is better than sex

Thursday, September 30, 2004

Wednesday, September 29, 2004

A column in the Toronto Sun presents a comparison I've heard a lot of conservatives make recently:

Comparing U.S. President George Bush with Winston Churchill may seem a stretch. Yet there's a parallel -- not with Churchill of the war years, when he was the "free" world's most admired leader, but with Churchill of the 1930s when he stood alone, warning about the rise of Nazism.No.

Then, pacifism was rampant in Britain and Europe. Hitler's aggression was rationalized by wishful thinking. Peace at any price.

Except for Churchill. He began warning that the Nazis must be stopped when they occupied the Rhineland in 1936 He urged an alliance of Britain, France and the Soviet Union to stop Hitler's expansion. He was called a warmonger, an enemy of peace, reviled in print and in speeches. Few stood with him.

History has proven Churchill right.

With the U.S. election entering the home stretch, Bush is under the same sort of attacks for his war on terrorism.

The 1930's were the time of a fundamental debate in England and America: aggressive intervention vs. isolationism.

This isn't the debate we're going through right now. No one in the mainstream left makes the claim that the US does not need to wage war against the terrorists. No one in the mainstream left makes any sort of general objections to intervention abroad in protection of international security.

The argument made by virtually everyone on the left is: fighting terrorism does not mean invading random countries. Wishful thinking on the part of the Bush administration aside, there was no collaborative relationship between Al Qaeda and Iraq; nor between Iraq and any other group conducting terrorist attacks on Americans. Getting bogged down in urban guerilla warfare in nations that did not sponsor terrorists only hurts the ability of the US to fight the war on terror.

(This argument, despite its apparent simplicity, is willfully misunderstood all the time on the right, and characterized as pacifism or appeasement.)

This is why all the repeated comparisons to Churchill make no sense: it is as if Churchill advocated invading Russia in punishment of Hitler's occupation of the Rhineland. Thats why all the meaningless posturing at the GOP convention - vote for Bush because he is "clear on terrorism" - makes no sense either; I'm glad Bush is enlightened, but his foreign policy and counter-terrorism policies have been a dismal failure.

Tuesday, September 28, 2004

From William Saletan's Catastrophic Success, in Slate:

In 1999, George W. Bush said we needed to cut taxes because the economy was doing so well that the U.S. Treasury was taking in too much money, and we could afford to give some back to the people who earned it. In 2001, Bush said we needed the same tax cuts because the economy was doing poorly, and we had to return the money so that people would spend and invest it.

Bush's arguments made the wisdom of cutting taxes unfalsifiable. In good times, tax cuts were affordable. In bad times, they were necessary. Whatever happened proved that tax cuts were good policy. When Congress approved the tax cuts, Bush said they would revive the economy. You'd know that the tax cuts had worked, because more people would be working. Three years later, more people aren't working. But in Bush's view, that, too, proves he was right. If more people aren't working, we just need more tax cuts.

Sunday, September 26, 2004

It turns out that Bush did learn something in college after all...

Ms. Hughes writes that she was once so frustrated that she asked Mr. Bush how a speech should be written. He scrawled out for her, she recounts, that it should have "an introduction, three major points, then a peroration - a call to arms, tugs on the heartstrings," then a conclusion, which "is different from a peroration." When Ms. Hughes asked how he knew all that, Mr. Bush replied, "The History of American Oratory, at Yale."

Saturday, September 25, 2004

Eugene Volokh worryingly cites the following from a Johnathan Rouch column on free speech:

In June, the FEC ruled that the Bill of Rights Educational Foundation, an Arizona nonprofit corporation headed by a conservative activist named David Hardy, could not advertise Hardy's pro-gun documentary ("The Rights of the People") on television and radio during the pre-election season. The FEC noted that the film featured federal candidates and thus qualified as "electioneering communication." Hardy, according to news accounts (I could not reach him by phone or e-mail), yanked the film until after the election.There are, apparently, quite a few instances of the FEC preventing people from marketing overtly political documentaries on TV and radio stations in this election cycle due to the passage of McCain-Feingold the year before.

What I don't understand is why any of this is worrysome. Forget about the legal definition of free speech for a second. Just think of the concept - free speech. What does it mean? My gut response is that it means the right to say whatever you want to anybody you want. Does that include the right to broadcast messages over public airwaves?

Its not obvious that it does. The UK, for example, restricts use of public airwaves far more stringently than the US does - sometimes preventing the media from reporting key parts of national stories; its campaign finance laws and restrictions on political advertising are many times more stringent. Are people in England any less free?

It seems like, due to the phrasing of the first amendment and other accidents of history, many things became legal under the rubric of free speech that are a stretch of the free speech concept itself - things like the ability of millionare candidates to dramatically outspend their opponents by self-financing their campaigns, as well as the rest of the provisions of Buckley v. Valeo.

Friday, September 24, 2004

From a note in today's Times,

The Republican Party acknowledged yesterday sending mass mailings to residents of two states warning that "liberals" seek to ban the Bible. It said the mailings were part of its effort to mobilize religious voters for President Bush.I don't mean to hold Bush responsible every time a low-ranking Republican party official comes up with a crazy idea - but patterns of incidents like this illustrate the extent to which mudslinging and appeals to ignorance are the core of the Republican strategy.

The mailings include images of the Bible labeled "banned" and of a gay marriage proposal labeled "allowed." A mailing to Arkansas residents warns: "This will be Arkansas if you don't vote." A similar mailing was sent to West Virginians.

The current administration produces figures that are way off base and cites them in support of its policies - surprise, surprise.

Wednesday, September 22, 2004

A question for Kofi Annan: if the Iraq war was illegal because it did not have approval of the security council, what about Kosovo?

Wednesday, September 15, 2004

More Alan Keyes! From a story in the Tribune,

...Keyes denied that he has engaged in name-calling in his campaign. But he likened Democratic opponent Barack Obama to a "terrorist" because Obama, a state senator, voted against a legislative proposal pushed by abortion foes...

From a Times article noting that its OK to deliberate a jury verdict while drunk,

...a 1987 United States Supreme Court decision involving a jury that... drank, used cocaine, smoked marijuana, sold drugs to one another and slept through a trial that one juror called "one big party." In that case, the court ruled: "However severe their effect and improper their use, drugs or alcohol voluntarily ingested by a juror seems no more an 'outside influence' than a virus, poorly prepared food or a lack of sleep."

Tuesday, September 14, 2004

Ugh.

A television journalist was shot dead as he made a live broadcast from Baghdad yesterday when United States helicopters fired on a crowd that had gathered round the burning wreckage of an American armoured vehicle.Click to see the picture, subtitled "An Iraqi boy joins the celebration around the burning US vehicle."

Mazen al-Tumeizi, a Palestinian working for Al-Arabiya, one of the main Arab satellite television channels, was among 12 people - all believed to be civilians - killed in the incident on Haifa Street...

Tumeizi was describing the incident on camera when two helicopter gunships were seen flying down the street and opening fire. Tumeizi was hit by a bullet and doubled over, shouting: I'm dying, I'm dying." About 50 people were wounded...

Through the day, United States officers offered contradictory accounts of the incident and ordered an investigation.

"As the helicopters flew over the burning Bradley they received small arms fire from the insurgents in the vicinity of the vehicle," said Major Philip Smith of the 1st Cavalry Division. "Clearly within the rules of engagement, the helicopters returned fire..."

However, witnesses said there were no Iraqi fighters in the area at the time.

An interesting excerpt from Sex in History by Gordon Rattray Taylor:

...we begin to see, not immorality as such, but a completely different system of sexual morality at odds with the Christian one [during medieval times]: a system in which women were free to take lovers, both before and after marriage, and in which men were free to seduce all women of lower rank, while they might hope to win the favours of women of higher rank if they were sufficiently valiant. Chrestien de Troyes explains:

"The usage and rules at that time were that if a knight found a damsel or wench alone he would, if he wished to preserve his good name, sooner think of cutting his throat than of offering her dishonour; if he forced her against her will he would have been scorned in every court. But, on the other hand, if the damsel were accompanied by another knight, and if it pleased him to give combat to that knight and win the lady by arms, then he might do his will with her just as he pleased, and no shame or blame whatsoever would be held to attach to him."

As Briffault comments, however, the first part of the rule does not seem to have been regarded so strictly as the poet suggests. Traill and Mann say, "To judge from contemporary poems and romances the first thought of every knight on finding a lady unprotected was to do her violence." Gawain, the pattern of knighthood and courtesy, raped Gran de Lis, in spite of her tears and screams, when she refused to sleep with him. The hero of Marie de France's Lai de Graelent does exactly the same to a lady he meets in a forest - but in this case she forgives him his ardour, for she recognizes that "he is courteous and well behaved, a good, generous and honourable knight".

Monday, September 13, 2004

This is my nominee for the most amusing Wikipedia article ever.

The Times runs an interesting piece today on one of Stanley Milgram's lesser known experiments:

Thirty years ago, they were wide-eyed, first-year graduate students, ordered by their iconoclastic professor, Dr. Stanley Milgram, to venture into the New York City subway to conduct an unusual experiment.

Their assignment: to board a crowded train and ask someone for a seat. Then do it again. And again.

"As a Bronxite, I knew, you don't do this," said Dr. Jacqueline Williams, now an assistant dean at Brooklyn College. Students jokingly asked their professor if he wanted to get them killed.

But Dr. Milgram was interested in exploring the web of unwritten rules that govern behavior underground, including the universally understood and seldom challenged first-come-first-served equity of subway seating. As it turned out, an astonishing percentage of riders - 68 percent when they were asked directly - got up willingly.

Quickly, however, the focus turned to the experimenters themselves. The seemingly simple assignment proved to be extremely difficult, even traumatic, for the students to carry out.

"It's something you can't really understand unless you've been there," said Dr. David Carraher, 55, now a senior scientist at a nonprofit group in Cambridge, Mass.

Dr. Kathryn Krogh, 58, a clinical psychologist in Arlington, Va., was more blunt: "I was afraid I was going to throw up."

When the Times makes up news stories out of thin air, it usually precedes them with titles like "White House Letter," or "News Analysis," as a way to tell its readers that nothing worth of reporting is contained in the story.

The latest "White House Letter" by Elizabeth Bumiller is puzzling. Entitled "Before Friendly Audiences on the Trail, a Looser, Livelier Bush Appears" the article provides a long record of Bush's gaffes before critical audiences,

There is also no disputing that Mr. Bush can falter in front of more skeptical audiences, as he did at a convention of minority journalists in Washington last month.Bumiller, however, notes that when Bush is speaking to a group of pre-selected Republicans he seems to be much more relaxed (duh):

The president got so twisted up in response to a question about tribal sovereignty - "tribal sovereignty means that it's sovereign'' - that the crowd started laughing at him.

Last Monday at a rally in Poplar Bluff, Mo., the president was into his usual riff against malpractice lawsuits when he said, without missing a beat, that "too many Ob-gyns aren't able to practice their love with women all across the country'' - an apparent crossed wire with the president's stump speech to religious groups, in which he invariably says that government cannot put love in a person's heart.

The day before, in Parkersburg, W.Va., Mr. Bush said that he asked Congress last September for $87 billion to help pay for "armor and body parts'' in Afghanistan and Washington.

And two days before that, the president mangled a favorite line about Mr. Kerry and the Democratic vice presidential nominee, Senator John Edwards, who were two of four senators to vote for the use of force in Iraq but against the $87 billion spending package.

"Two of those four,'' Mr. Bush cheerily concluded, "are my running mate and his opponent.''

But on the campaign trail, where the invited crowds are kept friendly because opponents are sometimes arrested for wearing anti-Bush T-shirts or dragged from events by their hair, there is a different President Bush. He is looser and livelier, a former Andover cheerleader who has learned how to rouse the crowd...Incredibly, the article then goes on to conclude that Bush is damn good on the campaign trail:

"I wish he was half as good a president as he is a campaigner,'' said Representative Rahm Emanuel, Democrat of Illinois, a former top aide to President Bill Clinton.Let's see: Bush screws up so hopelessly in front of critical audiences that his handlers eject anyone who is not a supporter from the campaign trail. However, before cherry picked Republican audiences, Bush actually does OK. How exactly does one get to the conclusion that Bush is good?

But there is no disputing the president's enthusiasm for this part of his job, particularly now that polls show him leading, and the way the invited crowds lap up his colloquialisms, malapropisms and Texas twang. (It intensifies west of the Mississippi.)

Even some Democrats begrudgingly give Mr. Bush good marks for his style on the stump.

"He doesn't have the stamina of a Clinton or the charisma of a Reagan, but when he's on his game, and he's not tired, he has a folksy, down-home approach that works for him,'' said Paul Begala, the CNN talk show host who worked in the White House for Bill Clinton and is now informally advising Mr. Kerry's campaign.

Isn't the very point of campaigning to win over votes that you did not have? And given that President Bush is speaking to Republican activists in these events, his success must be measured by the coverage generated in the press. And Bumiller's story, with its long catalogue of gaffes and screw-ups, its ruthless allusions (Bush is good because "he was a cheerleader at Andover" - did you know Bush used to be a cheerleader? You do now) seems to undermine the very point it is making.

How much longer will US troops remain in Japan? It seems like every few months or so there is a popular outrage at some act committed by US troops. Granted, this has been going on for decades, but it seems like we are approaching a point where the presence of US troops will become unapalatable:

For years, Okinawans have tolerated the deafening thud-thud of United States Marine Corps cargo helicopters over schools, playing fields and apartment buildings near the fence of one of the busiest military airfields of the Western Pacific.

Some shrugged when one helicopter spiraled from the sky on Aug. 13, banging into a university building, its rotor gouging a concrete wall, its fuselage exploding into an orange fireball. Miraculously for this congested city of 90,000, no one was killed, and the only people injured were the three American crew members.

But what really galvanized residents of this sultry tropical island were images of young American marines closing the crash site to Japanese police detectives, local political leaders and diplomats from Tokyo, but waving through pizza-delivery motorcycles.

One month after the crash, that fast-food delivery image - part truth, part urban myth - was strong enough to help to draw about 30,000 people on Sunday for the biggest anti-base protest in Okinawa since those a decade ago protesting the rape of a 12-year-old schoolgirl by three American servicemen.

It seems like not enough Russians have seen Episode II:

President Vladimir V. Putin ordered a sweeping overhaul of Russia's political system today in what he called an effort to unite the country against terrorism. If enacted, as expected, his proposals would strengthen the Kremlin's already pervasive control...

Under Mr. Putin's proposals, which he said required only legislative approval and not constitutional amendments, the governors or presidents of the country's 89 regions would no longer be elected by popular vote but rather by local parliaments — and only on the president's recommendation.

Seats in the lower house of the federal parliament, or Duma, would be elected entirely on national party slates, eliminating district races across the country that now decide half of the parliament's composition. In last December's elections, those races accounted for all of the independents and liberals now serving in the Duma.

My natural impulse when I encounter a piece about Shakespeare is to skip it - flip the page, change the magazine. Most likely it is just repetition of what we all learned in high school or, hardly better, vague phrases about Shakespeare's genius.

Which is why I was surprised at how good this piece is.

Sunday, September 12, 2004

I wish the media was not so intent on reporting the detail-by-detail occurence of events but rather focused instead of the larger stories. A good example: a story run by the Times today on the protests following the removal of Ismail Khan (pictured above) by the Kabul government.

Khan, a warlord who ruthlessly ruled Herat prior to being overthrown by the Taliban, has returned to being Herat's

Given that the major problem of postwar Afghanistan is the powerlessness of the central government and the return of the reign of the warlords, the apparently succesful removal of Khan represents a tremendous step forward. You wouldn't figure this out from the Times piece, which, failing to provide any context for Khan's removal, concentrates on gathering reactions to a few hundred protestors (who, anyway, were most likely among those with financial ties to Khan's government).

Thursday, September 09, 2004

From Who Needs Harvard? by Gregg Easterbrook:

...what if ... the idea that getting into an elite college makes a big difference in life—is wrong? What if it turns out that going to the "highest ranked" school hardly matters at all?

The researchers Alan Krueger and Stacy Berg Dale began investigating this question, and in 1999 produced a study that dropped a bomb on the notion of elite-college attendance as essential to success later in life. Krueger, a Princeton economist, and Dale, affiliated with the Andrew Mellon Foundation, began by comparing students who entered Ivy League and similar schools in 1976 with students who entered less prestigious colleges the same year. They found, for instance, that by 1995 Yale graduates were earning 30 percent more than Tulane graduates, which seemed to support the assumption that attending an elite college smoothes one's path in life.

But maybe the kids who got into Yale were simply more talented or hardworking than those who got into Tulane. To adjust for this, Krueger and Dale studied what happened to students who were accepted at an Ivy or a similar institution, but chose instead to attend a less sexy, "moderately selective" school. It turned out that such students had, on average, the same income twenty years later as graduates of the elite colleges. Krueger and Dale found that for students bright enough to win admission to a top school, later income "varied little, no matter which type of college they attended." In other words, the student, not the school, was responsible for the success.

Tuesday, September 07, 2004

Paul Krugman's latest column is rather good. An excerpt:

The best book I've read about America after 9/11 isn't about either America or 9/11. It's "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning," an essay on the psychology of war by Chris Hedges, a veteran war correspondent. Better than any poll analysis or focus group, it explains why President Bush, despite policy failures at home and abroad, is ahead in the polls.

War, Mr. Hedges says, plays to some fundamental urges. "Lurking beneath the surface of every society, including ours," he says, "is the passionate yearning for a nationalist cause that exalts us, the kind that war alone is able to deliver." When war psychology takes hold, the public believes, temporarily, in a "mythic reality" in which our nation is purely good, our enemies are purely evil, and anyone who isn't our ally is our enemy.

This state of mind works greatly to the benefit of those in power.

One striking part of the book describes Argentina's reaction to the 1982 Falklands war. Gen. Leopoldo Galtieri, the leader of the country's military junta, cynically launched that war to distract the public from the failure of his economic policies. It worked: "The junta, which had been on the verge of collapse" just before the war, "instantly became the saviors of the country."

The point is that once war psychology takes hold, the public desperately wants to believe in its leadership, and ascribes heroic qualities to even the least deserving ruler. National adulation for the junta ended only after a humiliating military defeat.

George W. Bush isn't General Galtieri: America really was attacked on 9/11, and any president would have followed up with a counterstrike against the Taliban. Yet the Bush administration, like the Argentine junta, derived enormous political benefit from the impulse of a nation at war to rally around its leader.

Another president might have refrained from exploiting that surge of support for partisan gain; Mr. Bush didn't.

And his administration has sought to perpetuate the war psychology that makes such exploitation possible.

Step by step, the fight against Al Qaeda became a universal "war on terror," then a confrontation with the "axis of evil," then a war against all evil everywhere. Nobody knows where it all ends.

What is clear is that whenever political debate turns to Mr. Bush's actual record in office, his popularity sinks. Only by doing whatever it takes to change the subject to the war on terror - not to what he's actually doing about terrorist threats, but to his "leadership," whatever that means - can he get a bump in the polls.

Monday, September 06, 2004

From an interview Alan Keyes gave to radio host Mike Signorile:

KEYES: A homosexual engages in the exchange of mutual pleasure. I actually object to the notion that we call it sexual relations because it is nothing of the kind.

SIGNORILE: What is it?

KEYES: It is the mutual pursuit of pleasure through the stimulation of the organs intended for procreation, but it has nothing to do with sexuality.

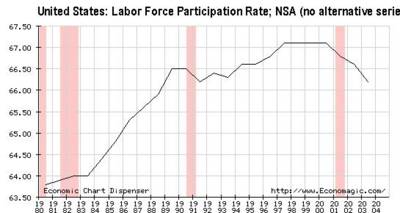

Tim Worstall notes that the current unemployment rate - 5.4% - would have been considered pretty good from 1980-1995, and speculates that structural changes in the US economy are the main cause of the change in perception.

The problem with looking at a single statistic like the unemployment rate is that it doesn't tell the whole story; one of the main problems today is the millions of discouraged workers who are no longer looking for jobs. A quick glance at the labor force participation rate (see chart above) reveals that the job situation is not the worst since '95, its the worst since '89.

The spat between Matthew Yglesias and Glenn Reynolds is rather amusing.

A recap: Yglesias writes about the Russian hostage situation,

The situation, clearly, can only be resolved by Russian concessions on the underlying political issue in Chechnya. At the same time, in the wake of this sort of outrage there will not only be no mood for concessions, but an amply justified fear that such concessions would only encourage further attacks and a further escalation of demands. I don't see any way out for Russian policymakers nor any particularly good options for US policymakers. Partisanship and complaints about Bush's handling of counterterrorism aside, this business is a reminder not only of the horrors out there, but also that terrorism is a genuinely difficult problem -- I think we've been doing many of the wrong things lately, but no one should claim it's obvious what the right way to proceed is.Reynolds interprets this, incredibly, as a call to surrender to the terrorists, paraphrasing Yglesias' post as follows:

Don't worry -- there's a solution: "The situation, clearly, can only be resolved by Russian concessions on the underlying political issue in Chechnya."After a criticism from Yglesias, Reynolds tries to justify his idiotic interpretation:

Matthew Yglesias emails to say that I've misquoted him above, and demands an apology. Er, except that the quote -- done via cut-and-paste, natch -- is accurate. Here it is again, cut-and-pasted, again. "The situation, clearly, can only be resolved by Russian concessions on the underlying political issue in Chechnya."Referring to Yglesias' rejoinder, Reynolds writes

I guess that Matthew means it's out of context, or misrepresents his post. Maybe it misrepresents what he meant to say...But I can't figure out what Matthew could have meant that would make the statement above a misrepresentation of his meaning...

Does that clear things up? Not to me. The only solution is concessions, which we can't make? Okay.As they say, it is difficult to make a man understand something when he is paid not to understand it.

How good are my political instincts? I'm about to find out: just bought a bunch of Kerry contracts on tradesports.com at 40.0 (i.e. I pay $4 per contract and get $0 if Bush wins and $10 if Kerry wins).

Saturday, September 04, 2004

Ouch. Post-convention polls by Time and Newsweek give Bush, respectively, a 10-point and an 11-point lead.

Two thoughts:

First, this discounts the claim, peddled by Democrats after the Democratic convention, that Kerry's small convention bounce is due to the ultra-polarized electorate.

Secondly, there has been much discussion around the blogosphere of various mathematical models used to predict election turnout. Fitting models to things is easy - as an applied math guy I should know - enter the data, run some best fit algorithm, and immediately you have a prediction for the future. But is there any reason to believe elections can be modelled in this manner? Trying to model, say, interarrival times of customers in a business as a Gaussian variable will give you bad results no matter how much you work it -because interarrival times are exponential. Not every approximation you come up with will match reality.

In fact, this swing - a 7 point lead for Kerry three weeks ago into an 11 point lead for Bush now - without any measurable change in the variables that go into these models - suggest that election outcome is a phenomenon which cannot be modelled using macroeconomic variables and other such data. I know little about this line of research, but has anyone ever made an argument for these models that did not go along the lines of "picking these parameters, the error in the previous 10 elections is small, so it will probably be small in the next election?"

Anyway: I, actually, did not think Bush's speech would have a large impact. I saw party spin that falls flat of reality - things in Iraq are going terribly and the more Bush pretends everything is hunky dory, the more disconnected he seems from the real world. The american people seem to disagree.

Thursday, September 02, 2004

This is pretty much how I feel about the Republican National Convention.

Wednesday, September 01, 2004

In the pre-Iraq war days, conservatives often trafficked in these two loosely-sourced claims:

1. France and Germany oppose American action in Iraq because they have secretly violated UN resolutions by trading with Iraq and are afraid an invasion would uncover evidence of this.

2. Terrorism can not exist without states who sponsor it; taking out nations that funnel money to terrorists would inevitably lead to the end Al-Qaeda and similar groups.

Conservative magazines (weekly standard, national review) and weblogs (instapundit, best of the web) routinely used these points in virtually every foreign policy note. Perhaps a bit of retrospection is in order, no?